Further only the forest

Two forest Bryansk villages, Chukhrai and Smelizh, are connected not only by a bumpy six-kilometer road, but also by a common history: both in the Great Patriotic War were in the

very center of the partisan movement; both were burnt down by the Nazis in 1943 and then rebuilt by local residents; both, after enlargement, were part of the same kolkhoz. But there are no longer kolkhoz, no shops, no schools, and the population both there and there has declined significantly.

It is all the more surprising that in recent years the indigenous people who left them in their time began to return to these villages, and moreover, natives of other places began to come for permanent residence. I went here in the summer of 2021 to understand why, as well as to find out how they used to live here and how they live now.

I WAS DRAWN HERE BY MY SOUL

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, thousands of villages in Russia were depopulated. A special statistical term was even invented for them: “rural settlements without population”. Chukhrai could suffer the same fate. But by some miracle, this remote village, surrounded on all sides by forest and swamps, in which there are more empty houses than residential ones, continues to live. The mobile shop hasn’t arrived for a long time, the wells have rotted, and the gas has not been installed – but it lives.

Only three of the indigenous inhabitants of the village remained: Tonya the Pochtarka, Nastya Shamornaya and Vasily the Baptiste (there were two main surnames in the village – Presnyakovs and Balakhonovs – and it was customary for local residents to give each other street nicknames).

Antonina Ivanovna Balakhonova from 1975 to 2009 worked here as a postman (that’s why they call her Pochtarka), and although then her daughters took her to live in their city, a few years later she returned back to her house. “I was drawn here by my soul,” – she explains.

Her husband died back in 81st, she runs the whole household herself. Almost nothing is left of the household – just chickens and a vegetable garden, and even from those there is one frustration: either the potatoes freeze, then the carrots will rot, than the hare will eat all the cabbage, then the fox will take the chicken away. And you can’t buy much for a 10,000 rub pension: “So you are trying to distribute this pension to everything: food, grain, chickens, pills. You pull and pull – not enough for anything. “

It is especially strange to hear about such a paltry pension when you find out what kind of work it was to be a postman in a remote village. In the spring or in the autumn rains, it was impossible to walk or drive along the forest road, so she walked around. The water was sometimes so high that she often had to take off her boots and wade through especially deep sections of the path. How many times did she fall and walk all wet. In the snow, in the frost – it was also difficult. And that’s just for the mail. Once a month she went to get a pension for fellow villagers even further, to Krasnaya Sloboda. In the winter, she returned after dark. Who would agree to such a job now?

But Antonina Ivanovna is more fond of remembering good things. For example, how the movies were brought. How they danced to the accordion. How in the spring flood, the water divided the village into four parts and its inhabitants swam across the streets in boats, with jokes and songs. How in the Apple Savior and Easter, women with children gathered in the morning and walked all day through the forest and meadows, 15 km away, to Trubchevsk to serve in the church, and the next day back. “There were a lot of people,” Antonina Ivanovna says. – And now some have moved away, while others have died. As long as God has extended his life to everyone, that is how much man lives. “

WITHOUT PASSPORT AND PENSION

Nastya Shamornaya (Anastasia Mikhailovna Presnyakova) has been living without a passport for a long time. She lost the old Soviet one, but refused the new one. When she was nevertheless persuaded to formalize it, it ended with the fact that she burned anew passport in the oven, saying that she did not need anything from the state. She refused a pension too. She lives on what God will send, how people will help, that she herself will grow up.

Perhaps for this reason, Anastasia Mikhailovna leads a secretive lifestyle hidden from prying eyes – sometimes she does not even let her fellow villagers into the house: they knock on her window, but she does not seem to hear. I knocked too, but she “did not hear” me either. And there would have been nothing for me to tell about her if one day I had not met her on a forest road – she was walking from Smelizh to Chukhrai with full bags – and when I stopped the car and offered to give her a lift, she agreed.

As it turned out, Anastasia Mikhailovna went to a neighboring village for cabbage seedlings. More people live there and surpluses remain, which kind people share . “Now I will plant cabbage,” she says happily, never ceasing to thank me for stopping. And when I called several names of her fellow villagers, she became quite kinder, and I asked to visit her. But she was embarrassed: “It’s shameful in my house, I live very poorly, for the reason that I already have such an age, I was born in 1946.” She didn’t let me in.

According to her, she has many relatives both in Russia and in Ukraine, but neighbors say that no one visits her. She lives alone for a long time.

BEES AND GOD

I was told about Vasily Balakhonov even before I first saw him. That every Sunday he goes to the regional center of Suzemka to the church of Evangelical Christians-Baptists (for which he was nicknamed “Vasya the Baptist”). That he has two adult daughters, one in Bryansk, the other in Murmansk. That his first wife died long ago, and he parted with the second and now also lives alone. And the main thing is that he makes delicious honey, for which people even come from other villages. But when we met him (at Antonina Ivanovna’s house), the first thing he told me was that there was no honey: “It’s cold, what kind of honey are you talking about? There are no bees. ” “How not, Vasil? I heard – they were flying and buzzing ”– Antonina Ivanovna entered the conversation. But it turned out that these were “alien bees”, not from Chukhrai.

That evening, passing by Vasily’s house, I saw him on the roof, fixing a new television antenna (lightning hit the old one).

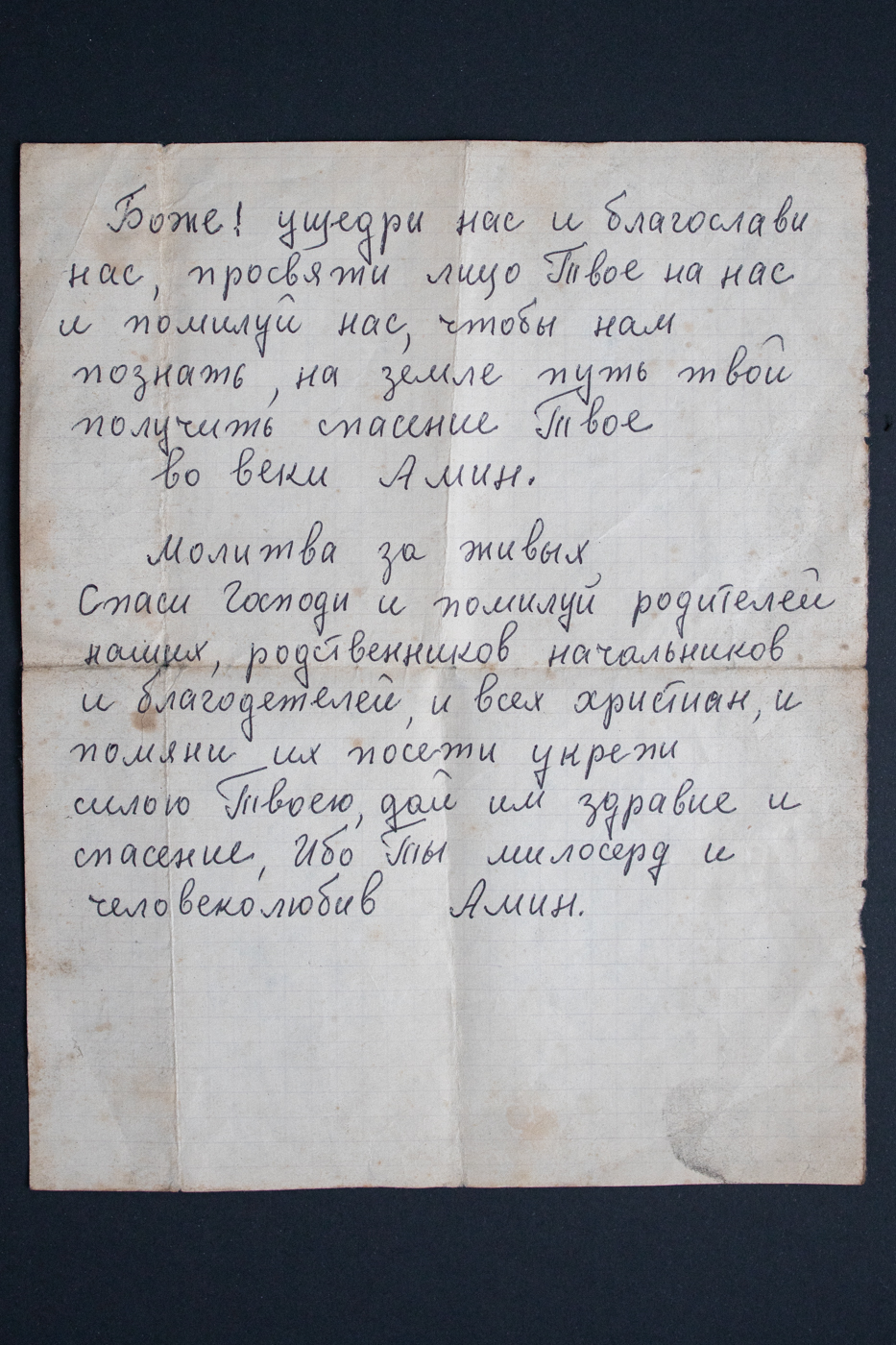

We got to talking, and Vasily told me his story about how he came to the Baptist church. Then he turned 35, he worked as a driver on a collective farm, and somehow during the spring field work a woman gave him the New Testament. He leafed through it and found the following words: “And whoever wasn’t in the book of life was thrown into the lake of fire.” “Am I included in this book? – thought Vasily then. – And who writes in it?” And so this thought penetrated him, that right up to tears. A strong desire to pray came. Then he knelt right in front of the car and began to ask God for forgiveness for his sins.

Later, in the fall, Vasily first came to the Baptist church service, and since then he quit drinking, quit smoking and for almost 30 years has been attending the service: “God changed my heart, changed my life.” When I asked why he chose the Baptist faith, Vasily replied: “There is true teaching. And Orthodoxy does not teach the Bible. ” And after a while, when we were already saying goodbye, he added: “Come back in a month, you will eat honey.”

WOODLAND FAIRY

In addition to the three indigenous inhabitants of the village, there are also new faces in it. Irina Ptitsina moved here from Moscow six years ago. How many people do you know who gave up a well-arranged life in a big city for the sake of living in a remote village? Irina, a former lawyer, is one of those. “My life is one continuous project,” she says. Born on Lake Baikal, she admits that she has always been drawn to the treasured site.

Once she decided to carry out the main project of her life: to settle in the village and do what her soul lies in. The soul lay to nature, to folk traditions, to gathering. But she understood that she alone would not be able to lead such a life, which requires constant physical labor, and solved this issue in her usual business manner: she advertised on Vkontakte (social network) about finding a partner, describing in detail what kind of man she needed. So she found Vadim, who was then living in Suzemka. Together they went on a journey through the villages, and when they arrived in Chukhrai, they realized that this was the right place in which they would like to live. Together they built a house, together they got a job in the reserve (less than 2 kilometers from the village there is a cordon “Staroye Yamnoe”).

Vadim continues to work there as an inspector even today, and Irina found herself another occupation: in one of the old houses, which they bought from the heirs of former residents, she creates a House-Museum of Rural life. The museum first opened in 2018, but at the time of my arrival, it was undergoing renovations and a new exposition was being prepared. In addition, Irina organized a center for the rehabilitation of wild animals “Forest House”, which began with a baby roe deer transferred to her to foster care by colleagues from the reserve. And then she also created a workshop “Forest Fairy Tale” for the production of natural cosmetics and decorative wood products. Thanks to all this, Irina, like other residents of the village, also got her nickname – “Woodland fairy”.

In the near future, Irina plans to make a guest house at the museum, in which visitors could stay and touch the past: cook in a Russian oven, use old items from the museum’s collection.

Local residents are quite fond of their new neighbors. “Oh, they are good people, – says Antonina Ivanovna. – You turn to them when you need to drive somewhere or buy something: bread, butter, sugar, pills – they will never refuse, very kind people. God sent us such people here.”

In addition, Vadim and Irina solved one of the main problems of the village – the lack of drinking water. They drilled a 60-meter well with their own money and now local residents no longer have to carry water in bottles from other places.

ONE OF US

Igor Petrovich Shpilenok, the founder and first director of the Bryansk Forest Reserve, can no longer be called a visitor – he settled in Chukhrai 30 years ago. At first he lived in the abandoned cordon, then he moved to the village itself. It is difficult to overestimate his contribution to the survival of the village. The forest road to Smelizh after the collapse of the collective farm turned into a swamp, in which even caterpillar vehicles sometimes got stuck. It became a pass again thanks to Shpilenok’s efforts. If you need a technique to plow a garden or any other help, locals also turn to him. He has the largest farm in the village: it contains not only chickens, but also geese, goats, bees and even horses.

Igor Petrovich is known far beyond these places, and not only thanks to his work on the creation of the Bryansk Forest Reserve. He is a professional traveler and naturalist photographer, the author of several photo books, including a two-volume book dedicated to the reserves of Russia (the result of his four-year auto-expedition). Therefore, he is often not at home. But I was lucky enough to find him there, albeit not for long. The only thing I regret is that the scope of this article does not allow me to tell about him in more detail. However, a book would not have been enough for that either.

IN ONE HANDS

Smelyzh was more fortunate in terms of communications than Chukhrai – after many years of appeals by local residents to various authorities, an asphalt road was finally built here, and in 2012 – the long-awaited gas. During the war, Smelizh was considered the partisan capital, next to it was the main headquarters of the united partisan detachments of the Bryansk forests, an airfield and a hospital (now there is a memorial dedicated to partisans and pilots there). In 2015, the village received the title of “Settlement of Partisan Glory.”

But otherwise Smelizh suffered the same fate as Chukhrai: after the closure of the collective farm, the young people left these places, the fields were overgrown, the four-year school was closed, and in 2015 the only store was closed too.

Ekaterina Ivanovna Gutorova worked in this store for seventeen years.

Just like Antonina Ivanovna in Chukhrai, she is the main keeper of the traditions of this place. He knows everyone, welcomes everyone – both his own people and visitors. “She will never let a person out on the street hungry. Whoever enters the hut – she immediately calls: sit down, eat”, says Antonina Ivanovna about her. They have a lot in common. Ekaterina Ivanovna, too, was left without a husband early and alone raised two children, a son and a daughter. Alone continues to run the household, or, as she says – “in onе hands.”

Talking with Ekaterina Ivanovna, I learned that the names of many objects in these places often differ from the generally accepted ones. At the same time, some of them in different villages are called differently, even in such close ones as Smelizh and Chukhrai: “We have skhodtsy (or porch), in Chukhrai – ganki; we have a cane, they have a dubéts. ” A hoe in Smelyzh is called a kapanitsa, a barn is a punya (or punka), a cow bell is a balabonka. Borrowings from the Ukrainian language are often encountered in speech – the proximity of the border affects.

Ekaterina Ivanovna told how the villagers solve their pressing everyday issues. The nearest large settlement, Suzemka, can be reached by bus, which runs three times a week: on Tuesday, Friday and Sunday. They go mainly to the hospital, to church, to visit relatives. An ambulance and firefighters are also called from Suzemka. On Tuesdays, a grocery mobile shop arrives, and on Thursdays and Sundays, bread is delivered separately.

According to her, no more than 30 indigenous villagers live here now. Many of them returned from distant places such as Surgut, Tynda, Murmansk.

RIVER MISTRESS

Larisa Vasilievna Sinyavskaya returned to her native village from Khabarovsk. The site on which her house is located is adjacent to the river, which she loves very much and feels like its real mistress.

The river, a tributary of the Nerussa, is called by the locals Krivaya (“the curve”), although this name cannot be found on the maps. Previously, Nerussa approached the village itself, but over the past few decades it has moved more than a kilometer away from it.

Fishing is not prohibited here, but Larisa Ivanovna and Ekaterina Ivanovna’s grandson Vladik, who joined her, now and then checked the snares and fishing nets set by other fishermen in order to release the captured small fry. At the same time, a young pike was rescued, hunting for fish and unsuccessfully jumping out of the water onto a water lily leaf. It was lucky that the river mistress checked her possessions at this time.

RESERVE

The fate of Chukhrai and Smelizh is not unique, in the neighboring villages everything is the same: collective farm lands have long been overgrown, farm buildings have been destroyed, and there is practically no work. Do the locals hope that agriculture and livestock will return here someday? No, each of them relies only on himself. But despite this, no hopelessness is felt in conversations with them. The forest, the river, the rich flora and fauna of these places make life here self-sufficient. And after the creation of the «Bryansk Forest» reserve in 1987 (in 2001 it was given the status of a biosphere reserve), the prospect of ecological and tourist development of this territory appeared, and now it is visited not only by residents of the Bryansk region, but also by other regions of Russia (according to data of the reserve, in the first half of this year alone, more than 8 thousand visitors were registered).

The reserve also contributes to the preservation of the historical past. So, on the territory of its central estate, an exposition of historical wooden products by local craftsmen was created, and nearby, in a pine forest, there is a museum of platbands. Platbands were collected from the deserted and dilapidated houses of the villages that surround the boundaries of the protected zone of the reserve – as a memory of the leaving peasant life and the people who lived here before. In addition to Chukhrai and Smelizh, these are the villages of Krasnaya Sloboda, Berezovka (Chern), Terebushka, Gerasimovka and Yamnoye.

But history is not only about the past, it is also about now. Thanks to the heroes of this story and other caring people – local residents, volunteers, reserve staff – the forest villages of Chukhrai and Smelizh continue to write their history.

Chukhrai, Smelizh 2021

All images and text © Oleg Kolimbet

Comments are closed.